skip to main |

skip to sidebar

25th ANNIVERSARY: BATMAN (d. Burton)

“They’re saying to me, these record guys, it needs this and that, and they give you this whole thing about it’s an expensive movie so you need it. And what happens is, you get engaged in this world, and then there’s no way out. There’s too much money. My major concern is that there is so much awareness and hype. I keep thinking, ‘I hope there’s a movie attached to all of this’.” — Tim Burton

What is hype, exactly? Where does it come from? Newspapers use the word to refer to the the publicity blitzes concocted by the studios —”studio hype.” The studios, on the other hand, use it to describe the self-induced feeding frenzy of the press — ”media hype.” The film director, meanwhile, sits in the middle, observing that it has a “life of its own.” Hype, it seems, is something a catch-all, a nonce-word, covering a multitude of sins, none of them ever your own. I anticipate, you expect, others hype. It’s a bit like trying to work out where air comes from.

Even its commonly presumed etymology is fake: “We live in a world of hyperbole,” said a Doubleday editor in 1980. '”Hyperbole has become so common that we now refer to it by a cozy contraction. We call it 'hype.' We decide to apply it, as if it were a wax compound for shining up a car.” But hype is not a shortening of “hyperbole” but of ''hypodermic needle'', and refers to the hopped-up state of drug users; when newspaper columnist Billy Rose praised a 1950 movie for having “No fireworks, no fake suspense, no hyped-up glamour,” his assumption was not that hype was something applied to a movie’s surface, buffing it up to a nice shine; but something internal, intravenous — which is much the way it works in Hollywood: As Will Rogers once remarked, “The movies are the only business where you can go out front and applaud yourself”, in which case the blockbuster is the only species of movie in which the hype is at its loudest within that movie itself. One of the more curious aspects about the hype for Batman, for instance, is that it never quite cleared. After all the hype, that’s what Batman turned out to be about: it was about hype.

“Tell your friends, tell all your friends,” whispers Batman to his first criminal catch, before letting them go, having realised that the benefits of good word-of-mouth far outweigh the benefit of having two more petty criminals behind bars. He then gets involved with newspaper photographer Vicki Vale ( Kim Basinger), who ensures that Batman’s name is spread city-wide, and it is the quality of Batman’s media coverage, far more than his actual deeds, that most enrages the Joker, flushing him out of hiding.

“Can someone please tell me what kind of a world we live in where a man dressed as a bat gets my airtime!” he complains, before shooting up his TV set. “Wait’ll they get a load of me!” he says and hits back with a PR campaign of his own, hijacking the airwaves to run a series of advertisements for himself — parodies of the hard-sell adverts of the fifties, with Batman in the opposite corner, representing the matte-black, soft-sell eighties. This is how the central battles in Batman are played out, not on the streets, but at press conferences, across the airwaves and in the newspapers. It is a PR war for the soul of Gotham city, and it resembles less the battle between two superhero colossi, than it does a presidential race, with two candidates endlessly finessing their public personae. What kind of a movie it is where all the villain wants to do is be more popular than its hero? It goes some way to explaining why Jon Peters had so much trouble trying to inject some genuine antagonism into the actual meetings between the Batman and The Joker: they’re like two presidential candidates who have somehow slipped their entourages, and accidentally met, away from the spit and fury of the hustings, only to find themselves getting along fine. There’s nothing between them personally. It’s all for the folks back home.

The one thing you don’t see much of in Batman, though, is folk. For all the energy that Batman and the Joker expend to win the hearts and minds of Gotham, it’s a strangely underpopulated place: at a press conference in front of the town hall, a gaggle of extras do their best to suggest a pullulating crowd, but Burton’s heart is not really in it — he doesn’t really have the bullying instinct for crowd scenes. He can’t summon the demagogic charge that you catch off all the great popular film directors — Capra, a great rouser of rabbles, or Hitchcock, never happier than when losing his heroes in a sea of faces. Nothing signalled Steven Spielberg’s entry into their hallowed company better than the crowd scenes in Jaws, with their ebb and flow of push and panic; there’s even a nun in there, just to remind us that this is the seventies. The thrill of the crowd pushes straight past Burton, who much prefers the sequestered darkness of the bat cave or the lonely eyrie of Batman’s perch atop a skyscraper — he is one of cinema’s natural loners, like Nicholas Ray. But he is no action director, and everything in Batman — its stop-start pace, its sputters of visual wit, its hero’s entrapment within a costume that gives him all the mobility of a neckbrace — suggests sulky self-sabotage on it’s directors part: revenge on a hero he just didn’t get. There’s not much to get, but you do need an honest instinct for hero-worship to shoot a comic-book, and Burton’s temperament is naturally mock-heroic; he can’t fake the tones — the athletic heft, the blockbuster high style — needed to sweep a movie like this along. Despite what he thought, “Death Wish in a batsuit” is almost exactly what it should have been. Reading the re-writes ordered up by Peters, its not to hard to figure out what was going on: the producers were using the Joker to smuggle back into the movie all the showmanship they felt their recalcitrant director was refusing to provide, and the movie belongs, in the end, to them. “Have fun, cause the party’s on me!” shouts Nicholson at the end, a version of Peters’ own high-rolling largesse, distributing cash to the greedy Gothamites, in what amounts to the movie’s last word on the delicate art of winning public favour: we can be bought.

And they were right — up to a point. The summer Batman opened was a one of the blockbuster’s landmark summers, just as 1984 had been before it, and whose records its casually smashed. “There’s a point beyond which no one can project,” said one Box-office analyst, “Anticipation is so high, the question this summer seems to be, how high is high?” The anticipation was guaranteed, however, if for no other reason than that 1989 saw the tidal wave of sequels set loose on the mid-eighties finally engulf cinemas — Lethal Weapon 2, Ghostbusters II, Karate Kid III, A Nightmare on Elm Street V, Star Trek V: The Final frontier, Friday the 13th part VIII, The Return of the Musketeers, Eddie and the Cruisers: Eddie Lives, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Police Academy V, The Fly II and Back to the Future II. “We’re thinking of calling it The Abyss II,” said Fox’s Tom Sherak, entrusted with the task of promoting one of the seasons few non-sequels, James Cameron’s The Abyss. If for nothing else, 1989 deserves a place in the history books as the year in which fewest people had an original idea for a movies than at any other time in Hollywood’s history.

What this meant for cinema-goers was an equally dense barrage of promotional campaigns, all vying for their attention. That year, the discerning movie-goer could choose between entering the James Bond License to Thrill sweepstakes to win a weekend getaway to Key West, the Indiana Jones Pepsi-Cola sweepstakes, and a Honey, I Shrunk the Kids McDonald’s promotion. You could win a trip to Tasmania courtesy of Young Einstein, you could follow the Great Balls of Fire publicity junket to Memphis. You could trot along to the Hollywood palladium to listen to Bobby brown and Run DMC sing the Ghostbusters theme, and try and win yourself the Ectomobile, all the while chewing on your Slimer Bubble Gum. Or you could go for a replica of The Batmobile, courtesy of a promotion on MTV, and jig around to ‘Batdance’ by Prince — ”an ode of the movie,” as he called it, which is rock-star speak for “they didn't use any of my tracks in their lousy movie but you might as well have them anyway.”

Alternatively, you could always go see a movie. Or the movie, for Batman soon became the blockbuster to see, unless you wished to announce your recent decision to join an order of Trappist monks.

It opened in 2,194 cinemas and took $42.7 million in its first weekend, ”the biggest opening weekend in history” proclaimed Warner Brothers, and proceeded to take $100 million in under ten days — another record, breaking Hollywood’s four-minute mile. But it also slid from pole position faster than any movie that has ever made that much money, too, taking just $30 million in its second weekend, a drop of about 25%, and the weekend after that, $19 million, a drop of 36%.. Blockbusters never used to fade like this — E.T.

had stayed at the top for 10 weeks (see graph), and increased its grosses as it went along, while Back to the Future had stayed up there for 13. But Batman came and went in the blink of an eye — that year, even Look Who’s Talking had greater staying power at the number-one spot. The most popular movie of all time was also just flavour of the month. Far more so than Jaws, it marked the beginning of the long, slow erosion of audience word-of-mouth — asked how much influence he thought the negative reviews in Variety and Time would have, Peters responded, “none” — and with it, a crucial shortening of the audience’s reaction times, which is to say our ability to respond to a movie, and then signal our collective approval or dislike by either staying away, or flocking to it in greater numbers. Who could tell, looking at Batman’s grosses, and their tail-off, to what degree people had enjoyed the film or not? More importantly, who was even interested in concluding anything from grosses of $251 million? “The audience can smell it faster than we can sell it,” Spielberg had said of E.T.’s release. As of 1989, we had just a little less time in which to do so. The art of selling bats had caught up with the art of smelling rats.

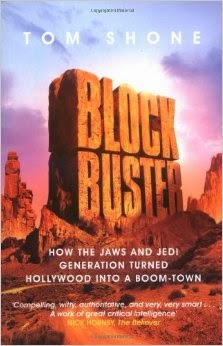

From my book Blockbuster

No comments:

Post a Comment